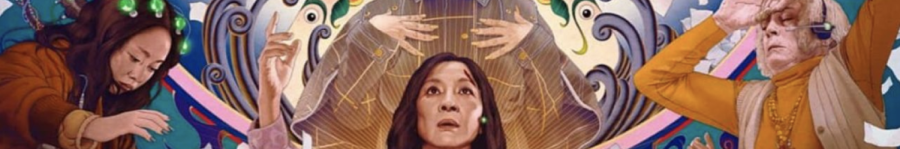

Bright and playful to the eye, this rendition of the 2024’s zodiac animal “Giáp Thìn” (Yang Wood Dragon) takes shape in the colors of ancient Vietnamese palettes. Created with respect for the spirit of traditional painting, the stylized connections of zodiac cycles and modernism are merged into one. Scattered but with intention, the five elements of life and birth reflect themselves behind the body of the subject. In fact, it was stated in history that in order to create a “lawful” artistic composition of life and order, every essential quality must be alongside each other.

Brown for earth, white for metal, umber for wood, cerulean for water, and crimson for fire—in the unity of life’s five elements, the bodily image of the dragon takes shape. Representing the year to come, the artwork reveals an ancient cycle of life and deep-rooted traditions, presented in the mode of fine art.

This is the work of the esteemed contemporary artist Nguyễn Tư Nghiêm. Born in 1918 in Nam Đàn, he was a late master in lacquer and oil painting, as well as a pastel and Dó paper artist that helped revolutionize and revitalize Vietnamese art traditions. In the contemporary scene of the 1950s onwards, many artists overlooked the value of traditional thinking during the midst of the Resistance War and the later inception of Western art methodologies. But Nghiêm, being the abstract painter (and revolutionary) he was, highly valued the rural essence of Vietnamese culture—ancient folklore, traditional dances, children’s games, and Đông Hồ paintings. To many, he is esteemed for his brilliant, timeless technique—a “pioneer in combining folklore with contemporary fine art,” stated a newswriter for Voice of Vietnam.

Alongside the visual themes, his personality and affinity for Vietnamese culture can be seen within his materials. Nghiêm’s early works were largely traditional lacquer pieces, and though the carving techniques are not present in his art, the vibrancy and vitality in the subjects are not buried or lost. Lacquer painting, or carving, is crucial in the makeup of Vietnam’s artistic culture, and Nghiêm, in his abstract approach to art, masters this in his early artworks, through which he revives the worth of traditional and local subjects.

Though in no way oblivious to Western modes, Nghiêm simply practiced contemporary techniques on traditional materials, as characterized when he began working with oil pastel and Dó paper later in life. His works were built on subjects of inspiration from Lý-Trần pottery and the Tale of Kiều to Thánh Gióng folklore and ancient pagoda structures. “The visual technique, though modern and stylized, evokes the climate of national beliefs – and neighboring cultures of Southeast Asia,” wrote Hà Tùng Long, a journalist for Dân Trí. Dó paper eventually became Nghiêm’s central medium, and from the 60s onwards, many alike began taking notice of his abstract approach to it, and adored his innocent, inclusive representations.

Artist Đặng Tiến writes: “[Some people who] do not grasp this emotion, think that he is picky or eccentric, but we can understand that the national character in Nguyễn Tư Nghiêm ‘s art is not an attempt to protect tradition, in a conservative will, but rather a supernatural need, from the subconscious to the conscious and expressed, incarnated, into art.”

Unlike many revolutionaries and painters of his time, who scarcely found unique insight into the language of the past, Nghiêm reinvented the artistic trends of colonial paintings and rules, and told special stories in his seemingly arbitrary works. At first glance, one may disregard the thought and the intention of each of his paintings, and especially in the modern art market, little consider his art for what it stands for—a linked communication with the beliefs and nature of the past. In an interview with Soi House, Nghiêm established his love for the colors of Vietnamese folklore. He said: “I am not attached to any foreign art, I just look in the nation and see in the nation there is humanity and modernity.

Giáp Thìn perfectly portrays Nghiêm’s ideology for art–its unbinding, free-going spirit pours from the painting; its vitality of color and space marks the 41st year in the sexagenary zodiac cycle. Widespread throughout Asian history, a measure of time in element and animal, the cycle is a primitive tool in Southeast cultures and not often remembered for its significance in the past. And yet, this system of understanding and other ancient innovations were what allowed modern civilization to progress, something Nghiêm took interest in showcasing.

Despite its singularity at the time, his belief in the value of Vietnamese traditions inspired a breakthrough in contemporary art, a new purpose for visual media. In place of the decorative works that were created to showcase current life or newfound techniques in the arts, Nghiêm’s interest in ancient themes restored respect for historical cultures. Inspiring scholars and up-and-coming artists alike, Nghiêm’s esteemed profile made an indent in Vietnamese history that has lasted long past his death—a leading figure in Vietnamese art, a master of making the ‘old’ new.